Belt v. Lawes The Sculptors’ Libel Case

Heather

Tweed

2016

2016

From Michaelangelo to Andy Warhol and

Damien Hirst, artists’ assistants have been an accepted part of the art studio system for

hundreds of years. Many carrying out manual or repetitive tasks, and some,

controversially, rather more. Questioning the authorship of an artwork had

rarely been so much in the public eye as the 19th century trial of Belt v

Lawes. After picking up a copy of The Graphic of 1882 from a Cardiff antiques

emporium, I decided to do a little research into this intriguing case.

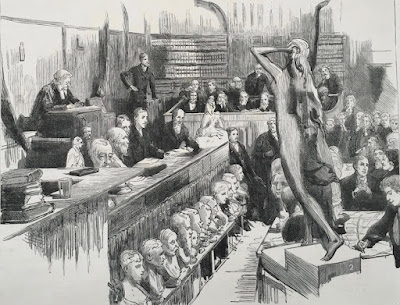

On November 18th 1882 more than thirty

heavy, life-size busts and sculptures carefully carved and modelled from

marble, stone and clay, clustered amongst the wooden benches and desks of the

High Court of Justice, Westminster Hall. The single largest exhibit was

Hypatia, in her larger than life nakedness, stepping forward from the dais,

left hand

brushing through her long hair, right

arm, raised palm upwards toward the heavens.

This sober palace of law had literally

been turned into a sculpture court.

Witnesses were called forward to have

their faces compared for likeness to the jostling busts. Sculpted heads were

held up before the Bench and jury, and an array of Royal Academicians were

grilled on the intricacies of sculpture techniques, aesthetics and the

technicalities of using assistants in the artists studio.

A star studded list of witnesses were

paraded in front of the jury including the Pre-Raphaelites, Lord Frederick Leighton, John Everett Millais, Lawrence

Alma Tadema and a

relatively young Hamo Thorneycroft. They all espoused what should have been

considered invaluable technical knowledge and aesthetic expertise. Most were

members of the famed Royal Academy and were experts in their field.

The notorious case of the 'ghost

sculptor' was now in full swing.

On August 20th 1881 Vanity Fair had

published an article questioning the provenance of sculptures carved and

modelled by the sculptor Richard Belt. The article accused Belt, an

artist favoured by Royalty, of passing

the work of sculptors François

Verhyden and Thomas Brock as his own creation.

Shortly afterwards a letter addressed

to the Lord Mayor was printed in Vanity Fair affirming the article to be true.

The three signatories, Charles Lawes, Charles Birch and Thomas Brock, were all

respected sculptors in their own right. Charles Lawes, or Sir Charles Bennet

Lawes-Wittewrong as he was later known, was the man behind the original

article. An Eton and Cambridge University educated Sculptor and athlete. His

father was the philandering first baronet of Rothampstead Manor, Hertfordshire.

After Cambridge, Lawes honed his craft

in London, apprenticed to J. H. Foley

RA, and rented a studio in Chelsea. He was the first president of the Society

of British Sculptors,

and his work at the Paris Universal

Exhibition of 1878 won him an honorable mention among the hundreds of world

class exhibits.

Richard Claud Belt was from a very

different background. The son of a journeyman blacksmith and a "domestic

worker”, Belt had been educated at a Baroness Burdett-Coutts charity school

then worked as a clerk and "machine boy". Nine years Lawes junior, he

was indentured to J. H. Foley's sculpture studio as an apprentice alongside

Lawes. Due to their different backgrounds and temperaments there may have been

some rivalry between the two. Belt had won a most prestigious commission, the

Hyde Park memorial to Lord Byron and his precious dog Boatswain. Belt was later

said, by some, to be the better sculptor.

Richard Belt, ‘The Whitechapel Oscar Wilde’, depicted in The Graphic of November 1882 with longer locks, prettier eyelashes and more pouting lips than the Illustrated London News image published on the same date!

Lawes and Belt both sculpted for grand

private and public commissions and portrayed many rich and famous personalities

as well as well known classical subjects. Now Belt needed to defend his hard

won reputation. He instigated a libel case against Lawes and the trial began in

January 1882.

In 1853 Charles Kingsley had written

*Hypatia* a fictionalized account of the eponymous pagan philosopher. This

explains the humorous illustrated reference to the inanimate figure declining

to swear on the bible in The Graphic of 1882. In order to prove Belt’s

validity, model and actress Elizabeth Brook, and another young woman who had

modelled for the statue, testified that it was only Belt who had stood before

them sculpting the piece.

Belt was charismatic and compelling in

the stand, the public liked him and he was known as the ‘Whitechapel Oscar

Wilde’. The

Isle of Wight Observer of January 1883, however, felt this was ‘not pleasantly

suggestive’ and described him as ‘bumptious’. His adoring band of female

acolytes obviously disagreed.

During December Lawes also accused

Belt of forging and using a £5 note. The Judge immediately dismissed the claim.

In his summing up, the judge intimated

that if a ‘layman’ jury could debate on the intricacies of the legal profession

then why should it not be the case that amateurs could be better at judging

artworks than professional artists. He was obviously not a great aesthete. The

jury had been in accord with this sentiment, as was apparent in their decision.

If Lawes had banked on relying on his aristocratic roots to find favour with

the Judge, he was sorely misled.

Lawes appealed, and the Appeal judges

he approached debated the evidence given by the long string of artists at the

first trial. The three judges were divided on the merits of a new trial and

plumped for the idea of reducing the damages from £5,000 to £500. Surprisingly

Belt agreed. Lawes refused. According to a later interview Lawes had tried to

settle out of court or to 'bribe me behind the scenes' as Belt put it. The

Court immediately ordered a new trial and Lawes objected, presumably

questioning their turn of heart.

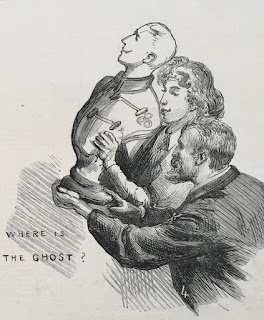

‘Her very likeness’ tongue in cheek jab at vanity as well as the case in hand

Eleven days of new deliberations by

the Court of Appeal brought forth an agreement with the original jury and

original damages amount. Lawes was also to pay for the costs of the trial and

two appeals.

Surprisingly he filed for bankruptcy.

Despite the generous allowance and other monies from his wealthy father, he was

declared bankrupt in May 1884. This was rescinded six months later. What his

well kept wife, (not to mention the Mistress who was exposed during one part of

the trial), thought of this turn of events is not recorded. Belt, the respected

sculptor, was exonerated. He also filed for bankruptcy.

In 1886 Belt was again in court, this

time for deception and fraud, alongside his brother Walter, a photographer. An

array of high class jewellers testified on behalf of Sir William Neville Abdy

that various necklaces, bracelets and other expensive items had been sold to him at vastly inflated prices by the

Belt brothers whom he had trusted as respected art dealers and artists.

Belt was sentenced for fraud and

endured 12 months hard labour, whilst his brother walked free. Belt and Lawes

both continued to sculpt although their reputations never quite recovered.

Sir Charles Bennet Lawes (1843-1911)

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

For a more in depth analysis of the

19th century social implications of the trial see:

Millais, Edmund Yates And The Case Of

Belt V Lawes,

P.D Edwards, Victorian Review, Vol.19, No 2 (Winter 1993) pp. 1-19 (Victorian

Studies Association of Western Canada)

Original page print from The Graphic,

Nov 18, 1882 p 532

Illustrated London News, Nov 18, 1882

Richard Claude

Belt’,

Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland

1851-1951

http://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/person.php?id=ann_1321801927

The Trial of Richard Belt and his

brother Walter:

Old Bailey Proceedings Online

(www.oldbaileyonline.org), March 1886, trial of RICHARD BELT WALTER BELT

(t18860308-376)

Book first published in 2012 from a

previously unpublished manuscript at the V&A:

Thomas Brock: Forgotten Sculptor of

the Victorian Memorial,

Frederick Brock, AuthorHouse (2012)

The Rowers Of Vanity

Fair

https://en.m.wikibooks.org/wiki/The_Rowers_of_Vanity_Fair/Lawes_CB

Newspapers and journals including The

Times, Western Daily Press etc accessed via

There is an additional article that I

must admit to not having read, as there is a prohibitive charge to access the

piece simply for a humble blog, however The Mapping Sculpture article draws on

the John Sankey piece:

The sculptor’s ghost - the case of

Belt v. Lawes,

John Sankey, Sculpture Journal, Vol.16, Issue 2 (December 2007)pp. 84-89 Access

via www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk

‘Hypatia

Refusing To Kiss The Book’

Richard Belt can be seen writing with a quill to the

right of the image.

©Heather

Tweed 2016